“Real artists don’t wait

For lawyers and officials

To give permission.“

Source: Mimi and Eunice

Mimi and Eunice’s “Copyright Reform” appears on the Mimi and Eunice website with a CC Free cultural Works License and the following statement: “Copying is an act of love. Please copy.”

Negotiating the Copyright Minefield

Despite the growth of Copyright alternatives such as Creative Commons globally, negotiating a safe path through the Copyright Minefield is no small feat for teacher librarians. Rather than merely providing a safe path, Cushla Kapitzke (2009) in “Rethinking Copyrights for the Library through Creative Commons Licensing” instead urges us to actively embrace the Scenic Tour – Extreme version!

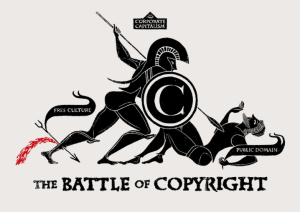

Throughout the article, Kapitzke stresses the chasm between the current culture of creativity and innovation AND the increasingly punitive and stringent realm of Copyright Law. She points out the farcical scenic backdrop: governments answering the pressures of the global economy on one hand with urgent calls for improved productivity through “cultural and scientific creativity” as with the other fist they tighten controls over Intellectual Property and Copyright. Commentary on this void is hardly the dominion of academia, as is graphically exemplified in the image below:

“The Battle of Copyright” [CC BY 2.0] by Christopher Dombres via Wikimedia Commons

The artist explains:

“The most famous episode of the terrible intellectual property war. A long time in the making, (first draft in 2007) a very complex issue, I did my best to make it clear. This illustration is an allegory of the battle between corporate monopolies and public domain for the extension of intellectual property. The legend of Achilles’ invulnerability served as inspiration, not the actual Trojan War. This design is copyright free.”

Colours and words: Mine, all mine?

Apparently the prevalence of copyright infringement litigation has led to the emergence of a “linguistic realty” (Kapitzke, 2009, p. 98)…? Imagine a commercial entity being granted “legalised ownership of commonly used words and phrases”!? Absurd as it may sound, Kapitzke (2009, p. 98) outlines several extreme cases where linguistic realty has become reality. For instance: A US accounting firm spends US$110 million for a monopoly on the word “Monday” and private database information firms consider their data on weather forecasts to be exclusive!

The mind boggles… although these cases did bring to my mind a long-ago episode of The Gruen Transfer which mentioned Cadbury’s supposed ownership of the colour purple. I gave the notion nothing more than a bemused eye-roll and slight head shake at the time, although in the light of Kapitzke’s article my latent indignation had the better of me. After a bit of poking around I was elated to dig up this report: “Cadbury to appeal against purple ruling”…

Congratulations, Federal Court, for so ruling on this preposterous 2008 claim to monopolise a colour… (but why did it take five years?!). And what happened in 2012 when it was the UK High Court ruling against Nestle for Cadbury’s right to exclusive use of Pantone 2685C??

Copyrighting for Creativity?

For illustration sake’s, let’s take a closer look at the Mission of the Australian Copyright Council. The ACC states:

“We believe in the values copyright laws protect: creative expression and a thriving, diverse, sustainable, creative Australian culture. A society’s culture flourishes when its creators are secure in their right to benefit from their creative work and when access to those creative works is easy, legal and affordable. Copyright effectively and efficiently enables this balance between protection and access.”

I confess I’m a mere novice, only dabbling in exploring this particular minefield, but I question whether increasingly tight Copyright laws can truly protect “creative expression” and a “thriving creative culture”. Copyright alternatives like Creative Commons can do it. But if we’re talking about Copyright Law as it stands today, the only entities who seem to thrive in that minefield are the large production and publishing companies (and law professionals of course), certainly not the struggling musicians, writers and artists who would probably prefer that their works be heard, read and sung…

Kapitzke ventures so far as to claim that strong copyright protection serves the governing authorities and the copyright industries in two ways: it “constructs a state of scarcity to keep prices high” and in driving the “so-called information/knowledge/creative economy”, it advantages “capitalist nation-states such as the United States and Europe” (Kapitzke, 2009, p.102).While Creative Commons enables the balance the ACC preach, Kapitzke (2009) maintains that it is the “regulatory frameworks” around Copyright that “have disrupted the historical balance between access and use of other people’s materials and diminished incentives for creativity.”

Teacher Librarians take the wheel

Kapitzke’s recommendations both surprise and delight me. Using contemporary social theory (namely, the work of Foucault), she advocates squaring the shoulders and tackling the minefield head on.

“Clearly, commercial piracy of cultural materials is wrong and should be prohibited, but regulatory environments that prosecute young people for tinkering with text (language, image, or sound) by sharing digital resources as part of their meaning-making universe are socially dangerous” (Kapitzke, 2009, pp. 102-3).

In Kapitzke’s view, we as educators must lift our heads and build a critical awareness, helping our students to analyse and evaluate the law, rather than cower in its shadow. Kaptizke’s approach to a critical copyright education is a three-pronged trident:

- Firstly, we must appreciate the “political economy of text production and distribution” within which we operate in the digital age. In the current climate of Web 2.0 opportunities driving an increasingly collaborative and participatory culture, traditional distinctions between producers and consumers are blurred. Taxonomies are no longer hierarchical and driven by experts but formed from and by networked communities.

- Our second front is building awareness and support of alternative copyright frameworks such as Creative Commons and open source products and tools, such as The Free Software Foundation. These growing initiatives better reflect the inventiveness and creativity of the current “rip, mix and burn” mashup culture.

- Finally, for schools to be “culturally and critically engaged”, we need to develop “ethical critique” within Copyright education. By “ethical critique”, Kapitzke honours Foucoultian discourse in her clarification of the term. She does not promote “exposing falsity” or “unmasking […] unfair purposes”. Rather, she espouses a “moral attitude, a way of thinking, an art of not being governed like that”. Our students have a right to question the “truth” of copyright law as it affects the nexus between knowledge and power.

“Copyright stands at the intersection of access to learning, literacy, fulture, knowledge and technology today” (Kapitzke, 2009, p. 105).

It is this final recommendation that conjures an image of the teacher librarian as an intrepid creativity crusader, fueling young stakeholder activists to seize their right to challenge those who construct laws that restrict their creative power and autonomy. “Restricting access to the raw materials of creative endeavor is culturally short-sighted and counterproductive” to enterprise and innovation (Kapitzke, 2009, p. 106).

Clearly the “scenic tour” of critical copyright education must be guided via the school library – “the oldest of creative commons for young people” (Kapitzke, 2009, p. 107). Despite continual urges for granting young people the “room to push the boundaries of language, sound and image”, Kapitzke is vague about precisely how to achieve such dizzying heights of young-people-power.

Please comment if you have any good resources to recommend that will encourage critical questioning and analysis of copyright regulation.

—————————————–

This post is one of a series on Copyright, Creative Commons and Popular Culture. You may also be interested in these two posts:

——————————————

Featured image: “Sulaymaniyah Minefield” by Tom Blackwell on Flickr [CC BY-NC 2.0]

References:

Kapitzke, C. (2009). Rethinking copyrights for the library through Creative Commons licensing. Library Trends. 58(1), pp. 95-108

Thanks to Max Barry and his Nation States forum for the Featured Image.

The Battle of Copyright 2011 (Illustration) by Christopher Dombres on Flickr

Once again Maria, interesting and thought provoking reading. I especially relate to the quote…

“we as educators must lift our heads and build a critical awareness, helping our students to analyse and evaluate the law, rather than cower in its shadow”.

This is so true for other types of social media and networking sites young people use. No use teachers, schools and policy makers burying their heads in the sand or completely blocking access. It is all about building awareness, responsibility and respect. Parents have such an important role to play as well.

Pingback: Copyright + Pop Culture = Creative Commons | The Grapevine

Pingback: Entering the Shadows: Making Sense of Copyright | The Grapevine

This blog is fantastic, great layout, and topics . Keep up the great work 🙂